In 1970, when an Italian priest named Antonio Polo came to the flyspeck Andean village of Salinas de Guaranda, it was an unknown place, even to the Spanish colonists of the 16th century. The Spaniards had steamed up from Peru in their conquest of the Inca Empire, right through southern Ecuador, and overlooked it.

“It wasn’t on any map,” shrugs Guillermo, a youthful guide for the local tourism co-op. “They never found us,” even though the town had been producing salt, a vital and coveted product, probably for thousands of years.

Father Antonio had bigger ideas than salt. Over the ensuing years, he inspired the community to form co-ops and establish a medley of businesses producing everything from cheese to chocolate, wool and alpaca yarn and clothing, sausages, dried mushrooms, and even artisan soccer balls, beautifully and laboriously handmade.

Next year, the town will mark the 50th anniversary of its economic and social rebirth that has spread to other villages even higher in the mountain páramos, and lower into subtropical climes. Thirty hamlets have added their mostly agricultural products into the co-op model that is so often central to local South American economies.

The most obvious symbol of success is Salinerito (“little guy from Salinas”), a brand well known for cheese, chocolates, and much more.

I arrived last week, grinding gears up the absurdly steep and narrow streets, to see two energetic volleyball games in progress in the town square barely big enough to hold them.

“It’s the only flat place in town,” explained Guillermo.

It’s also a good way to stay warm. The temperature hovered just above freezing for the duration of my 3-day stay, with howling seasonal winds that rattled corrugated roofs and made the walls of my hostel creak, day and night.

The natives barely seem to notice, any more than they heed the lack of oxygen at 11,600 feet elevation. They were born here, like Sherpas, while this visitor from the Low Country—only 7000 feet—feels like colossal lead weights have been strapped onto his shoes.

On that first early evening the insistent church bell rang for some time, and I saw people streaming from the sanctuary while others waited in the street outside, bundled against the blustery gusts tearing at their scarves. Then a casket emerged on the shoulders of pallbearers, joining a priest and altar boys for a procession that turned immediately through the gate of the old cemetery next door.

It was a reminder that this economic miracle is principally a community of living, breathing, and occasionally dying people, more so than a tourist destination. In fact, the tourists, while more than welcome, are not obvious—possibly because most of them are Ecuadorian.

The cheese factory is the star at the center of the co-op constellation, employing and buying milk from several hundred members. Some dairy farmers milk with machines, while others perform the job the old-fashioned way and deliver their product on the backs of patient burros.

Strict testing is in place to screen for mastitis and other impurities before the milk is pasteurized and the cheese-making process is underway. In the new facility, built five years ago to replace an aging one, workers dressed like surgeons labor in sunlight filtered through a blue overhead dome. There are sealed rooms for aging rounds of cheese for up to 12 months. That’s some very old cheese in a country where only fresh cheese is traditionally consumed.

Up a steep road—they are all steep in this town—sits a building where men throw armloads of sheared wool off a parked truck. Machines inside wash the wool, dry, card, and comb it, and spin it into yarn that is dyed in dazzling colors. The same happens with alpaca, and much of it goes to the local women’s weaving cooperative to be made into sweaters, hats, and ponchos for sale.

Then there is the chocolate factory, worthy of Willy Wonka (but notably lacking Oompa-Loompas). The climate is far too cold for raising cacao, so it’s brought up from steamy Esmeraldas on the Pacific coast, yielding rich chocolates for national distribution and increasingly for export, especially to Europe.

There is even chocolate infused with Pájaro Azul, a potent sugar cane liquor originating here in Bolívar Province. It contains secret ingredients such as orange leaves and tangerines, sometimes chicken broth, and produces a distinctive blue glow when held up to the light—as for a toast.

Across a street and up a treacherous concrete staircase (watch your head!) a family makes soccer balls. The process is complicated. An air bladder is wrapped with hundreds of feet of string in a perfect sphere, then covered with triangles and pentagons of thin leather, pressed in a heavy mold, baked in an oven, and chilled in cold water. As a final touch, a worker carefully inks the letters pressed into the surface, using something like a hypodermic needle.

The result is a genuine work of craftsmanship, priced high enough that you might want to keep yours on a shelf for people to admire. Not for some kid to scuff around a muddy field.

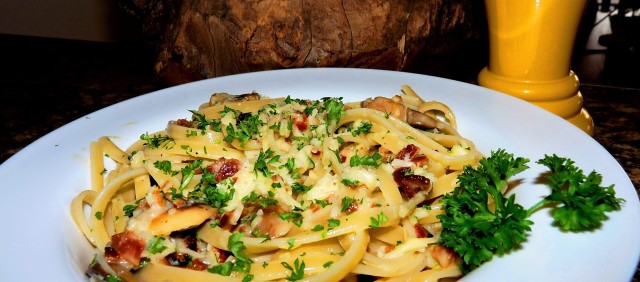

Local restaurants serve up a tribute to the Salinerito brand. I enjoyed pizza with a delicate crumbly crust and loaded with salami, ham, and cheese from just down the street. Later, a bowl of spaghetti bolognese as good as I’ve had anywhere, topped with grated cheese.

Why Italian cuisine? Is Father Antonio a foodie? These and other questions will have to wait for another time, because he was away on church business.

All good things must come to an end, and I picked my way carefully down through the streets, half of which are currently torn up for the installation of a sewer system.

And here I made my mistake.

It’s common knowledge that Ecuadorians are so eager to be of help that they will give you directions even when they don’t know the way. It’s one of the most delightful things about the people of this country. But any expat knows that you should keep asking until at least two answers match. I did not.

A man told me that the way I had come earlier was closed for paving, and said I should go in the other direction, and “turn right where they are cutting down a lot of pine trees.” The road had been down to one lane when I came in, so his story seemed plausible. I took his advice.

And this is the marvelous serendipity of travel, if you just give it a little time, and try not to be in a rush. Misdirection is opportunity, and the route the man had described transported me through breathtaking scenery, among high hills with clouds streaming over them, sharp boulders, and occasional landslides but otherwise a very fine road.

People in the red ponchos typical of this region walked along the narrow shoulders, herding alpacas, sheep, cattle, or burros, offering a friendly wave as I passed. There were wide vistas of expansive pastures, jagged rock formations, and widely scattered rooftops gleaming in the morning sun.

It was 40 minutes before I arrived at the next town and decided I probably needed to turn back. I asked a woman where I might find a gas station, thinking I could ask for directions there. She paused for a long time, and finally said, without conviction, that there was one near the town square. There wasn’t.

This was a woman who had never had a reason to visit a service station in her life. How I envy her.

But I saw a young man sitting in a doorway under a crudely hand-lettered sign indicating that this was a provincial bus stop. I told him my problem.

“Oh, you can get through that road,” he said. “They’re working, but you can squeeze past.” So I thanked him and turned to leave, but then asked, “What town is this?”

“Simiatug!” he exclaimed, and began singing the praises of his village. I’d like to go back one day.

I returned the way I had come, revisited the scenery and stopped for confirming directions from the tourism office in Salinas, and moved on toward home without difficulty. As an added bonus, I was able to snap a picture of spectacular, snow-covered Chimborazo volcano, Ecuador’s highest mountain, on a rare clear day, with green rolling fields in the foreground reminiscent of a Grant Wood painting.

As John Steinbeck so wisely said, “We don’t take a trip. A trip takes us.” This one was cold, uncomfortable, steep, oxygen-free—and unforgettable.

Moonset, Salinas de Guaranda, Ecuador

In hindsight, it’s difficult to remember the precise moment when things started to go so hopelessly wrong that they would eventually cross the line to hilarious, and beyond. Our first clue should have been the countenance of the harried waitress, who approached our table clutching the menus. She looked like a wild-eyed rabbit being stalked by a ferret. If she didn’t actually have a nervous twitch, she probably does by now. She scattered the menus toward us and darted furtively away as chaotic crashes erupted behind the kitchen door. Four heads swiveled, like owls, toward the new sound.

In hindsight, it’s difficult to remember the precise moment when things started to go so hopelessly wrong that they would eventually cross the line to hilarious, and beyond. Our first clue should have been the countenance of the harried waitress, who approached our table clutching the menus. She looked like a wild-eyed rabbit being stalked by a ferret. If she didn’t actually have a nervous twitch, she probably does by now. She scattered the menus toward us and darted furtively away as chaotic crashes erupted behind the kitchen door. Four heads swiveled, like owls, toward the new sound.